Constrained Quadratic Optimisation: 1.

The canonical problem

[this page | pdf | references | back links]

Return to

Abstract and Contents

Next

page

1. The canonical

problem

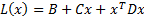

Constrained quadratic optimisation involves finding the

value of a vector  that

minimises a given penalty function

that

minimises a given penalty function  (or

maximises it, the two are interchangeable by replacing

(or

maximises it, the two are interchangeable by replacing  with

with

) subject to

some (normally linear) constraints, where:

) subject to

some (normally linear) constraints, where:

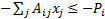

The constraints, in canonical form, are normally of two

types. There are  lower limit

constraints of the form

lower limit

constraints of the form  (by which we

mean that each

(by which we

mean that each  for

for  )

and there are

)

and there are  further

constraints of the form

further

constraints of the form  (by which we

mean that each

(by which we

mean that each  for

for  ).

).

In these definitions  is a scalar,

is a scalar,

is a vector

(or

is a vector

(or  matrix) and

matrix) and  is

an

is

an  symmetric

matrix, which is assumed to be non-positive definite if the problem is a

minimisation, and non-negative definite if the problem is a maximisation. A

non-negative definite (symmetric) matrix is one whose eigenvalues are all at

least zero.

symmetric

matrix, which is assumed to be non-positive definite if the problem is a

minimisation, and non-negative definite if the problem is a maximisation. A

non-negative definite (symmetric) matrix is one whose eigenvalues are all at

least zero.

The value of  is

irrelevant to the optimal value of

is

irrelevant to the optimal value of  so without

loss of generality can be taken as zero.

so without

loss of generality can be taken as zero.

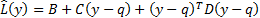

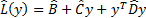

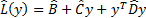

Problems with lower limits on each  that are

non-zero, say

that are

non-zero, say  can be

restated into the above form by a change of variables to

can be

restated into the above form by a change of variables to  resulting

in a new penalty function:

resulting

in a new penalty function:

Here  where

where  ,

,  and

and  . We

therefore merely need to alter

. We

therefore merely need to alter  appropriately,

and unwind the change of variables at the end of the optimisation process.

appropriately,

and unwind the change of variables at the end of the optimisation process.

Problems that involve ‘greater than’ or ‘equals’ type

constraints, e.g.  or

or  as

well as (or instead of) ‘less than’ type constraints can be converted into the

above canonical form by:

as

well as (or instead of) ‘less than’ type constraints can be converted into the

above canonical form by:

(a) converting each

‘equality’ constraint into two equivalent constraints, one being the

corresponding ‘greater than’ constraint and one being the corresponding ‘less

than’ constraint, altering  accordingly

(since if

accordingly

(since if  then

then  and

and

, and then

, and then

(b) inverting each

‘greater than’ constraint present into a ‘less than’ constraint by noting that

if  then

then  .

.

NAVIGATION LINKS

Contents | Prev | Next